Published 24 June 2025

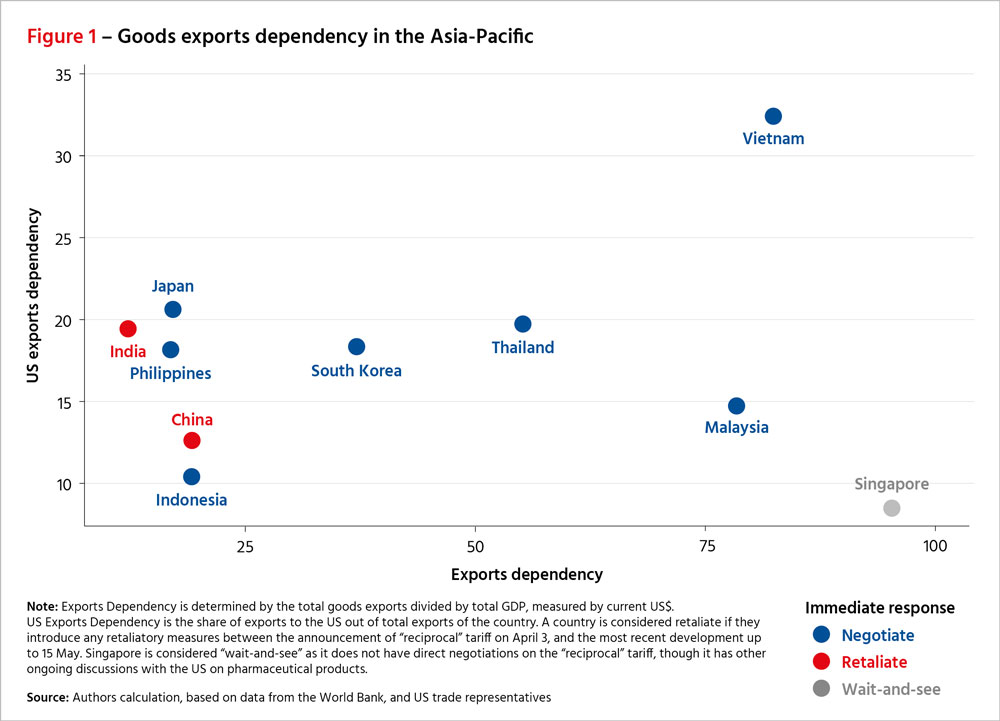

The responses of countries in the Asia-Pacific to Trump’s “reciprocal” tariffs are converging around three distinct strategies: negotiation, retaliation, or a wait-and-see approach. A closer analysis of the region’s export profiles and dependencies helps explain why these responses vary so significantly.

The resurgence of US protectionism under Trump 2.0 has reignited longstanding tensions in global trade, prompting a strategic recalibration across Asia-Pacific. As tariff threats loom large, countries in the region are reassessing their trade strategies.

The 90-day pause on most "reciprocal" tariffs, announced by Washington on April 9, and notably excluding China, offers a brief window for diplomacy. But it has not eliminated uncertainty. Instead, it has ushered in a transitional period in which Asia-Pacific governments must decide how to navigate the new international trade dynamics.

When examining the responses of countries to "reciprocal" tariffs, it becomes clear that regional reactions are converging around three primary strategies: negotiation, retaliation, or a wait-and-see approach. A closer analysis of the region’s export profiles helps explain why these responses vary so significantly. The degree of export dependency may shed light on why countries adopt different strategies to align with their trade interests.

Vietnam: High US export dependency, maximum diplomacy

Countries with high exposure to US markets are moving quickly to preserve trade ties. Vietnam, whose economy is among the most export-dependent in the region, with the US as its largest single export market, has taken pre-emptive steps to demonstrate goodwill and alignment with American trade priorities. On March 31, it issued Decree 73, lowering most-favoured-nation (MFN) tariff rates on essential goods to align its tariff structure with international norms and enhance trade competitiveness, particularly for US exporters who lack preferential access in the absence of a free trade agreement. At the diplomatic level, Vietnam has also been proactive. In a high-level meeting on March 14, Industry and Trade Minister Nguyen Hong Dien and US Trade Representative Jamieson Greer signed cooperation agreements and purchase contracts valued at US$54.3 billion, covering machinery, raw materials, aviation, energy, and petrochemicals. Further contracts worth US$36 billion are reportedly under negotiation, potentially raising total commitments to US$90.3 billion.

Extending beyond that, on March 27, ahead of any official announcement from the Trump administration on new trade policies, Vietnam moved to reduce import duties on several American goods, including liquefied natural gas, automobiles, and ethanol. The timing of these tariff reductions underscores Vietnam’s broader strategy to avoid punitive measures and reinforce its role as a responsible trading partner. While it may not have yielded immediate results, the "reciprocal" tariff rate alone does not determine the success or failure of Vietnam’s policy. It remains to be seen if Vietnam’s tariff diplomacy will work.

Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN: Moderate US export dependency, measured diplomacy

Japan, where 25% of exports go to the US, responded to US tariffs by ramping up trade talks. However, it is important to note that while Japan has signalled openness to certain trade concessions with the US, it remains firm in its goal of securing full tariff removal from the Trump administration and has notified the WTO of potential retaliatory measures.

South Korea and Malaysia, though moderately exposed, are engaging Washington with a view to mitigating the immediate shock. Malaysia is navigating the challenge with both bilateral diplomacy and regional leadership. As an export-dependent economy, Malaysia relies heavily on the US to absorb a significant portion of its semiconductor and electrical and electronics (E&E) exports. Recognising the vulnerability, Malaysia has been proactive in deploying its role as the 2025 ASEAN Chair to coordinate a unified regional stance. Under its leadership, ASEAN has agreed not to pursue retaliatory tariffs, instead reaffirming its commitment to a rules-based multilateral trading system through the World Trade Organization. The bloc has also endorsed the formation of an ASEAN Geo-Economic Task Force to assess long-term strategic implications, pledged to enhance supply chain resilience, and reinforced engagement not only with the US but also with other major trade partners.

China and India: Low US export dependency, retaliate

On the other hand, countries with lower export dependency on the US have shown a greater willingness to adopt a more assertive stance. India and China, both less reliant on the US as an export destination, have been more prepared to retaliate. China’s response has been more forceful. Excluded from the 90-day tariff pause, Beijing escalated its countermeasures, including export restrictions on critical minerals and the imposition of a 125% retaliatory tariff on US goods. This, in turn, prompted Washington to raise its tariffs on Chinese imports to 145%. Although these rates have recently been reduced to 10% and 30%, respectively, the mutual economic strain has made prolonged escalation politically and economically untenable for both sides. Though it is important to note that this comes after the country had attempted to negotiate, only for the US to proceed with raising import duties on steel and aluminium to 25%.

Singapore: Low export dependency, low tariff, wait-and-see

Singapore is perhaps the most structurally insulated. While it is the region’s most export-oriented economy overall, its exposure to the US market is relatively low. This gives it the flexibility to adopt a wait-and-see strategy, focusing instead on protecting its domestic industries against supply chain shocks.

What comes next?

As the 90-day tariff pause nears its expiration, policymakers across Asia are confronting two pressing questions. First, will the tariffs expand again? And second, more importantly, what kind of trade order will they be forced to navigate in the aftermath? The US actions post-pause will offer a critical signal, not only about whether tariffs are back on the table, but also about what kinds of responses Washington rewards or punishes. For many in the region, it will serve as an early test of whether the US can still be regarded as a credible and consistent trade partner.

With Washington’s protectionism far from settled, Asia-Pacific economies are bracing for a scenario in which the US is no longer a consistent anchor in global trade. Even close partners are preparing for friction. Far from waiting, they are negotiating, diversifying, and redesigning their trade portfolios for a more fragmented future.

Most countries are moving fast to lock in short-term stability. Countries like Vietnam, Japan, and Malaysia are pursuing active diplomacy to secure trade deals and prevent the imposition of the "reciprocal" tariff after the pause. These arrangements function as diplomatic hedges, as they aim to shield strategic exports from sudden tariff blows.

But alongside these efforts, a more fundamental shift is taking place. Countries are no longer simply managing exposure to the US market; they are actively rebalancing away from it.

The region is doubling down on alternative trade partnerships. Malaysia recently concluded a trade agreement with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and is reviving stalled FTA negotiations with both the European Union and South Korea. China, for its part, has signed a series of trade agreements and new memoranda of understanding with Southeast Asian countries, most notably Vietnam, Cambodia, and Malaysia, during President Xi Jinping’s tour of the region in mid-April. Meanwhile, India and the United Kingdom finalized a long-pending trade deal in early May, a process that had gained new urgency in light of escalating US tariffs.

What’s emerging is a threefold response to the tariff pause, and a preview of what comes after. First, supply chains are shifting to enhance resilience and diversification. Even before the tariff, multinational firms had been expanding their secondary production bases. China+1 strategies have been ongoing, particularly in the semiconductor and electric vehicles industries. The tariff will accelerate the trend of companies setting up multi-production bases to improve their supply chain resilience.

Second, trade governance is fragmenting. With WTO reform stalled and US leadership inconsistent, the world is moving away from multilateralism into regional and minilateral arrangements, including regional trade agreements like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for trans-Pacific Partnership, and bilateral FTAs. While countries remain committed to the WTO’s rule-based order, a rise of minilateral trade agreements will shape the region in the years to come.

Third, trade portfolios are being actively diversified. While countries still value US market access, few are betting on its reliability. Instead, they are anchoring their exports in a wider constellation of partners, across Europe, the Gulf, and within Asia itself. China, long ahead of the curve, now send more exports to the Asian countries than to the US. ASEAN’s upgraded Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) is also close to concluding.

The 90-day pause, in this sense, has already achieved something lasting, not by resolving uncertainty, but by clarifying it. Asia now sees the writing on the wall. The era of single-anchor trade diplomacy is over. Negotiation remains essential, but export diversification and more integrated trade partnerships within and beyond the region are the future of growth.

For the United States, how it moves next will matter. A return to sweeping tariffs could accelerate regional decoupling and reinforce perceptions that Washington is no longer a reliable economic partner. Conversely, a more constructive and conciliatory approach could help slow the fragmentation and begin to restore some measure of confidence.

However, for Asia-Pacific, the strategic pivot has already begun. The post-pause era will not be defined by whether tariffs go up or down. It will be shaped by how countries prepare for a trade world where diversification, not dependence, becomes the defining principle.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).